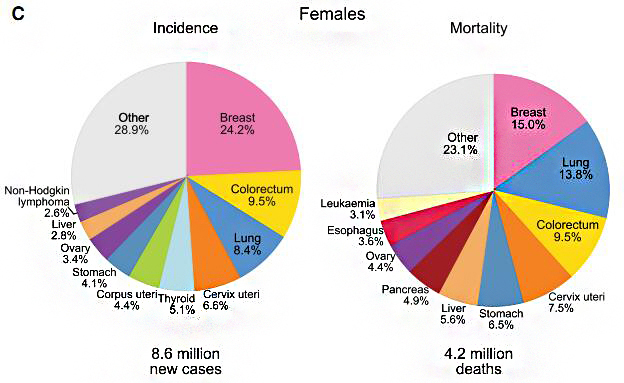

子宫颈癌是危害妇女健康的主要杀手之一,它是全球最致命但最容易预防的女性癌症类型。在全球范围内,每年有超过27万人死于子宫颈癌,其中高达85%的死亡病例发生在发展中国家 [1]。据WHO估计我国是世界上浸润性宫颈癌(ICC)发病人数第二多的国家(每年约有45,000例新发病例和25,000例ICC相关性死亡病例)[2]。

数据来源于发表在Ca-Cancer J Clin的“2018年全球癌症统计数据”

人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)是专性感染人表皮和粘膜的常见DNA病毒,是导致宫颈上皮内增生(CIN)和宫颈癌的主要因素。根据导致宫颈癌的危险度,HPV可分为低危型和高危型。高危型HPV主要导致宫颈非典型增生和宫颈癌,低危型HPV主要导致生殖器疣(如尖锐湿疣)。目前报道的HPV型超过100种,已知约35种涉及生殖道感染,其中15到20种为高危型或可能的高危型。对宫颈癌组织标本的研究发现,约99%的宫颈癌伴有HPV感染,其中HPV16和18的感染率最高,分别占到50%和20%,而HPV阴性者几乎不会发生宫颈癌。持续感染高危型HPV,尤其是HPV16、HPV18会导致高度子宫颈上皮内瘤变和宫颈癌的发生。对于具有正常细胞学宫颈但高危型HPV检测呈阳性的女性,4-7年内约有15%-30%的可能发生CIN2或CIN3。对于具有CIN3且未正规治疗的妇女,30年内有31.3%的患者成为宫颈癌。

Clifford等在2003年分析了全球各大洲85项总计10058例用PCR方法鉴定宫颈癌组织(宫颈鳞癌8550例,腺癌1508例)的HPV感染型别的研究。结果显示,子宫颈鳞癌中HPV16感染率最高,为45.9%-62.6%,HPV18的感染率为10%-14%,在亚洲,HPV58 (5.8%)和52(4.4%)是感染率仅次于HPV16和18的型别。子宫颈腺癌中HPV18感染率最高,为37%-41%,HPV16所占比例为26%-36%,HPV45占到5%-7%。

国际癌症研究机构(IARC)得出结论,宫颈癌筛查的基本手段除了细胞学检查外,HPV DNA检测是可以接受的选项。世界卫生组织(WHO)也建议利用HPV检测筛查预防女性子宫颈癌,对高危型HPV阳性感染者需要定期随访,而HPV阴性者,发病风险较低,可适当延长其筛查间隔。2013年美国宫颈和阴道镜病理协会(ASCCP)指南中更新了宫颈癌筛查流程,特别提出在HPV检测中应对 HPV16/18进行分型检测。因此高危HPV的诊断筛查以及HPV16、HPV18的分型检测,对于宫颈癌的预防与治疗有着非常重要的作用。

随着宫颈癌机理的阐明以及检测技术的发展,HPV检测在宫颈癌筛查中的地也越来越重要,2015年ASCCP发布的宫颈癌筛查指南明确指出,HPV检测可单独用于宫颈癌初筛。

文章中涉及图片部分来源于网络和参考文献,版权归原作者所有,如有不妥,请联系删除。

[1]. World Health Organization, Comprehensivecervical cancer control A guide to essential practice (Second edition)[eb/ol]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/144785/1/9789241548953_eng.pdf,2014

[2]. Ferlay J et al. GLOBOCAN 2002Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. 2004. Lyon, IARCPress.

[3]. Schiffman, M. H., H. M. Bauer, R. N.Hoover, A. G. Glass, D. M. Cadell, B. B. Rush, D. R. Scott, M. E. Sherman, R.J. Kurman, S. Wacholder, Stanton CK, Manos MM. (1993). Epidemiologic evidenceshowing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelialneoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 85: 958-964.

[4]. Kjaer, S. K., A. J. van den Brule, J.E. Bock, P. A. Poll, G. Engholm, M. E. and J. M. W. Sherman, and C. J. Meijer(1996). Human papillomavirus: the most significant risk determinant of cervicalintraepithelial neoplasia. Int. J. Cancer 65: 601-606.

[5]. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM,Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. (1999).Huma papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide.J Pathol. 189: 12-19.

[6]. Zur Hausen, H. (2000).Papillomaviruses causing cancer: evasion from host cell control in early eventsin carcinogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 92: 690-698.

[7] LorinczAT, Reid R, Jen sonA B, e t a l. H um an papi llom av iru s infect ion of th ecervix: relative risk associations of 15 comm on anogen ital types[ J] .ObstetGyn eco,l 1992, 79: 328~ 337.

[8] Lang J H.To receive the global chanllenge and copportunity for preventing cervicalcancer[ J ]. Chin J ObstetGynecol, 2002, 37 129.

[9] Smith JS,Lindsay L,HootsB, et al.Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer andhigh-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update〔J〕. Int J Cancer,2007,121 ( 3 ) : 621 -632.

[10] Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D,Moscicki AB, Smith RA, Eyre HJ, Cohen C; American Cancer Society. (2002).American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasiaand cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 52: 342-362.

[11] Wright, Thomas C. J; Schiffman, Mark;Solomon, Diane; Cox, J Thomas; Garcia, Francisco; Goldie, Sue; Hatch, Kenneth;Noller, Kenneth L.; Roach, Nancy; Runowicz, Carolyn; Saslow, Debbie. (2004).Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunctto cervical cytology for screening. Obstet Gynecol 103: 304-308.

[12] Rodriguez. Act Schiffman M, Herrero R , etal.Longitudinal study of human papillomavirus persistence and cervica intraepithelialneoplasia grade 2/3:critical role of duration of infection [J]. JNatl cancerInst ,2010 , 102(5):315 - 324 .

[13] McCredie MR, sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Naturalhistory of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women withcervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study [J]. LaneetOncol,2008,9(5):425-434.

[14] Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, etal. Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide:ameta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer, 2003,88(1):63-73.

[15]. Belinson SE, Wulan N, LiR, Zhang W, Rong X, Zhu Y, Wu R, Belinson JL. SNIPER:a novel assay for human papillomavirus testing among women in Guizhou, China. IntJ Gynecol Cancer. 2010 Aug;20(6):1006-1010.

[16]. Agorastos T, DinasK, Lloveras B, de Sanjose S, Kornegay JR, Bonti H, BoschFX, Constantinidis T, Bontis J. human papillomavirus testing for primary screening inwomen at low risk of developing cervical cancer. The Greek experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2005Mar; 96(3):714-720.

[17]. Cuschieri KS, Cubie HA. The role ofhuman papillomavirus testing in cervical screening. J Clin Virol. 2005; 32:S34-42.

[18]. Sankaranarayanan R, ChatterjiR, Shastri SS, Wesley RS, Basu P, Mahe C, MuwongeR, Seigneurin D, Somanathan T, Roy C, Kelkar R, ChinoyR, Dinshaw K, Mandal R, Amin G, Goswami S, PalS, Patil S, Dhakad N, Frappart L, Fontaniere B. IARCmulticenter study group on cervical cancer prevention in India. Accuracy ofhuman papillomavirus testing in primary screeningof cervical neoplasia: results from a multicenter study inIndia. Int J Cancer. 2004 Nov 1;112(2):341-347.

[19].American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Updated Consensus Guidelines for Managing Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors[eb/ol]. http://www.asccp.org/Portals/9/docs/ASCCP%20Management%20Guidelines_August%202014.pdf ,2014-08.

[20].Use of primary high-risk humanpapillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening:Interim clinical guidance.Gynecologic Oncology 136(2015):178-182.